- Messages

- 16,416

- Reaction score

- 10,331

- Points

- 288

Here's something you didn't know....

(1942 - 1945)

Places > Oak Ridge: Clinton Engineer Works

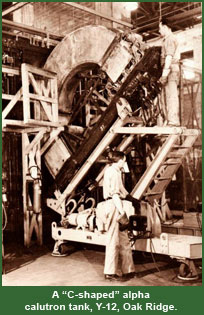

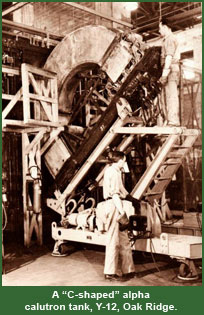

Silver withdrawals from the U.S. Bullion Depository at West Point, New York, began October 30, 1942. The MED took control of the silver in 1,000-ounce bars at West Point and shipped the bars in special guarded trucks to a casting plant in Carteret, New Jersey, where U.S. Metals Refining Company employees counted, weighed, melted, and cast the silver as cylindrical billets. Shipped, again by rail under armed guard, to the Phelps Dodge Copper Products Company extrusion plant at Bayway, New Jersey, the billets were extruded and rolled into strips 5/8 inch thick, 3 inches wide, and about 40 feet long, which were then cooled, trimmed, and coiled. The coils went by rail freight to the Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Shipments usually consisted of 6 sealed cars accompanied by not less than 3 armed guards in a special caboose. At the Allis-Chalmers plant, the silver was wound, suitably insulated, around the steel bobbin plates of the magnet coils. The completed magnet coils, welded inside sealed steel cases, were loaded on rail flat cars and securely blocked for shipment to the Clinton Engineer Works (Oak Ridge). No guard force was provided. Due to the perceived difficulty in accessing and making off with the silver, MED officials decided that better security would be achieved by sending unguarded units over different routes and time schedules.

Three shipments of silver strips were made directly to the Clinton Engineer Works from the Bayway plant. These were used to make the huge bus bars of solid silver, roughly a square foot in cross section and running around the top of the Y-12 racetracks. Fabrication took place in a restricted fabrication shop at Y-12. As the silver was needed, it was taken from a locked storage room, weighed, processed, re-weighed, and each piece stamped with an identification number. Armed guards accompanied the bus bar until it was permanently installed in the process buildings.

After the war, the Y-12 racetracks were dismantled and the silver returned to the U.S. Treasury. At the processing and fabrication facilities, workers under MED oversight disassembled and cleaned part by part the machines used, dismantled the melting furnaces, and swept and scoured all of the work areas. As a result, the MED could not account for only about one thirty-six thousandth of one percent of the borrowed silver. Most of this was unavoidable melt loss.

Y-12 SILVER PROGRAM

(1942 - 1945)

Places > Oak Ridge: Clinton Engineer Works

- The Choice of Oak Ridge, TN

- Oak Ridge Site Acquisition

- X-10 Graphite Reactor

- Y-12 Electromagnetic Separation Plant

- Y-12 Silver Program

- K-25 Gaseous Diffusion Plant

- S-50 Thermal Diffusion Plant

- Oak Ridge Town Site

- Construction Camps

- Life at Oak Ridge

Silver withdrawals from the U.S. Bullion Depository at West Point, New York, began October 30, 1942. The MED took control of the silver in 1,000-ounce bars at West Point and shipped the bars in special guarded trucks to a casting plant in Carteret, New Jersey, where U.S. Metals Refining Company employees counted, weighed, melted, and cast the silver as cylindrical billets. Shipped, again by rail under armed guard, to the Phelps Dodge Copper Products Company extrusion plant at Bayway, New Jersey, the billets were extruded and rolled into strips 5/8 inch thick, 3 inches wide, and about 40 feet long, which were then cooled, trimmed, and coiled. The coils went by rail freight to the Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Shipments usually consisted of 6 sealed cars accompanied by not less than 3 armed guards in a special caboose. At the Allis-Chalmers plant, the silver was wound, suitably insulated, around the steel bobbin plates of the magnet coils. The completed magnet coils, welded inside sealed steel cases, were loaded on rail flat cars and securely blocked for shipment to the Clinton Engineer Works (Oak Ridge). No guard force was provided. Due to the perceived difficulty in accessing and making off with the silver, MED officials decided that better security would be achieved by sending unguarded units over different routes and time schedules.

Three shipments of silver strips were made directly to the Clinton Engineer Works from the Bayway plant. These were used to make the huge bus bars of solid silver, roughly a square foot in cross section and running around the top of the Y-12 racetracks. Fabrication took place in a restricted fabrication shop at Y-12. As the silver was needed, it was taken from a locked storage room, weighed, processed, re-weighed, and each piece stamped with an identification number. Armed guards accompanied the bus bar until it was permanently installed in the process buildings.

After the war, the Y-12 racetracks were dismantled and the silver returned to the U.S. Treasury. At the processing and fabrication facilities, workers under MED oversight disassembled and cleaned part by part the machines used, dismantled the melting furnaces, and swept and scoured all of the work areas. As a result, the MED could not account for only about one thirty-six thousandth of one percent of the borrowed silver. Most of this was unavoidable melt loss.